📌 Key Takeaways

Most MTTR variance is decided in the first 60 minutes—not by technical skill, but by whether your team has a repeatable structure for roles, containment, and communication.

- One Incident Commander Eliminates Escalation Loops: Designate a single coordinator (not a troubleshooter) within five minutes to own the timeline, manage stakeholder communication, and execute the playbook—preventing the chaos of multiple engineers investigating conflicting hypotheses.

- Containment Before Root Cause Cuts Customer Pain: Roll back risky changes, use feature flags to disable problematic functionality, or isolate noisy components to stop the blast radius from growing—mitigation within 20 minutes often beats hours spent chasing perfect diagnosis.

- Scheduled Status Updates Protect Engineering Focus: Commit to predictable communication cadence (every 15-30 minutes) with a clear next-update time, even when there’s no progress to report—stakeholders stop calling when they trust the rhythm.

- Seven Measurable Behaviors Drive Faster Resolution: Track Time to Mitigation vs. Restoration, First Response Time, Handoff Latency, Update Cadence Adherence, and Page Efficiency to reveal which process gaps actually lengthen MTTR without requiring additional headcount.

- Quarterly Tabletop Drills Turn Playbooks Into Instinct: Run low-stakes simulations using free CISA exercise packages to test role clarity and decision-making under pressure—teams that practice structured response transform documentation into reflexive execution.

Structure beats speed. Prepared teams resolve incidents through disciplined iteration, not heroics.

For mid-market operations and IT leaders accountable for SLAs and cycle times who need to reduce MTTR without expanding on-call rotations.

The pressure hits hardest in the first 60 minutes. Your team scrambles to understand what broke, who should fix it, and what to tell stakeholders while the clock on your SLA agreement ticks forward. Most organizations lose the MTTR battle in this opening window—not because they lack talent, but because the first hour lacks structure.

Research into incident response patterns reveals a consistent truth: the behaviors teams execute in the first hour determine the majority of variance in mean time to resolution. When roles remain unclear and communication follows ad-hoc patterns, decision latency compounds. Teams waste critical minutes determining who owns the problem, which systems to page, and what constitutes useful status information. By the time clarity emerges, the incident has often escalated beyond its initial blast radius.

A structured first-hour protocol changes this dynamic completely. Organizations that pre-define ownership, establish paging discipline, and schedule status updates according to stakeholder needs consistently achieve faster stabilization without expanding headcount. This playbook provides that structure.

Why the First Hour Dominates MTTR

The opening phase of any incident creates a cascading choice architecture. Each decision point—who to page, what systems to check, how to communicate impact—either accelerates resolution or introduces friction that compounds throughout the lifecycle.

Three factors drive this phenomenon. First, cognitive load peaks when teams lack pre-established response patterns. Engineers waste mental energy on coordination rather than troubleshooting. Second, stakeholder anxiety amplifies fastest in the information vacuum of the early minutes, creating inbound noise that distracts responders. Third, containment opportunities close rapidly; the longer teams debate approach, the further the impact spreads across interconnected systems.

Organizations often attempt to solve MTTR through tooling investments or additional on-call rotations. These approaches miss the fundamental issue: process clarity matters more than resource allocation. A team of three engineers with a clear runbook and defined roles will consistently outperform a team of ten operating without structure.

The structured incident management approach defined in ISO/IEC 27035-1:2023 provides an internationally recognized framework for handling security incidents through distinct lifecycle phases. The Respond and Recover functions in the NIST Cybersecurity Framework 2.0 similarly emphasize structured response over ad-hoc heroics. According to NIST SP 800-61 guidance on computer security incident handling, establishing clear roles and communication protocols represents a foundational element of effective incident response. The framework emphasizes that preparation and procedural clarity reduce both response time and the likelihood of escalation.

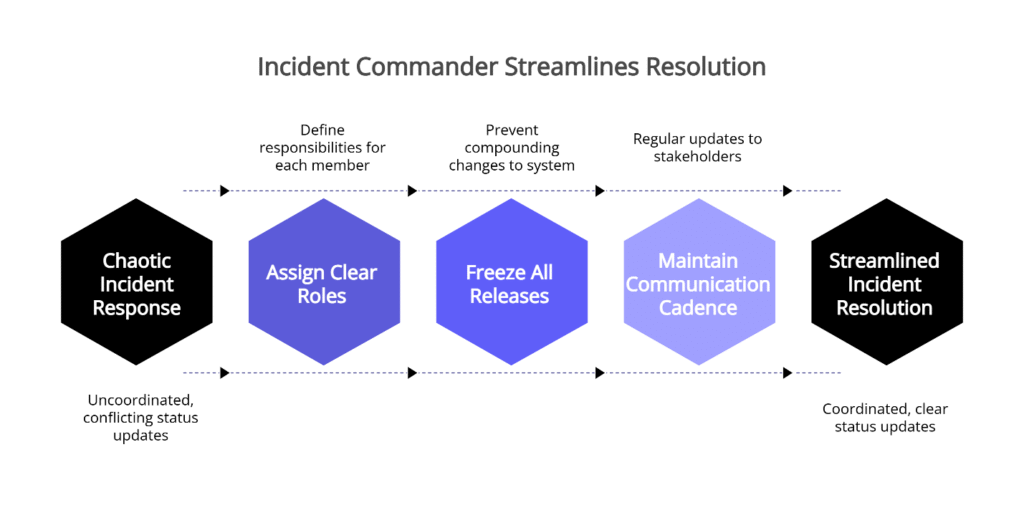

What “One Owner” Really Means

The single most impactful first-hour decision involves designating one incident owner—often called an Incident Commander. This role differs fundamentally from the team responding to the incident. The owner coordinates, not troubleshoots. Their job involves maintaining the timeline, managing stakeholder communication, and ensuring the response follows the established playbook.

Without this clarity, teams often fall into an escalation loop. Multiple engineers simultaneously investigate different hypotheses. Status updates conflict or contradict. Stakeholders receive different narratives from different team members. Each well-intentioned responder creates coordination overhead rather than resolution progress.

Consider a mid-market retailer that experienced checkout timeouts minutes after a routine feature toggle. The designated Incident Commander immediately declared a severity-one incident, assigned clear roles, and froze all releases to prevent compounding changes. While the Operations Lead isolated the misconfigured flag through systematic hypothesis testing, the Communications Lead sent a customer update at the 12-minute mark with the next update time clearly stated. The team met its communication cadence, avoided leadership interruptions, and restored service in 38 minutes. The following day, they ran a 30-minute review session to lock in process improvements.

Ownership assignment should happen within the first five minutes and follow a pre-defined rota based on incident type. The act of declaring an incident creates the authority to make containment decisions, page additional expertise, and represent the response to leadership. This formal declaration prevents the diffusion of accountability that lengthens MTTR.

The owner’s first action involves establishing the incident channel and inviting only the roles required for the specific incident type. This prevents the common pattern where concerned team members self-select into the response, creating noise without contributing specialized knowledge. Effective monitoring signals help the owner quickly assess which systems and roles require immediate attention.

Paging Discipline: Right Roles, Right Rota, Zero Heroics

Most organizations struggle with two opposing paging failures. Some teams under-page, leaving critical expertise offline while generalists struggle with unfamiliar systems. Others over-page, waking entire departments for incidents that require narrow technical knowledge. Both patterns increase MTTR.

A disciplined paging approach maps incident types to required roles before an incident occurs. The rota defines primary and secondary contacts for each system or service tier. When an incident begins, the owner pages according to type and severity level, not intuition.

Consider this distinction carefully. If the incident involves database performance degradation, the first page goes to the database specialist on rotation, not the entire infrastructure team. If the issue impacts customer-facing services, the owner pages the relevant service owner plus the communications lead, but not engineering leadership unless the incident meets predefined escalation thresholds.

This approach serves two functions. First, it reduces wake-up noise, which matters for team sustainability and on-call morale. Engineers who receive pages only for incidents requiring their expertise respond with better focus than those who field frequent false alarms. Second, it creates space for the actually required experts to work without coordination overhead from well-meaning but non-essential contributors.

Understanding your deployment environments helps the team determine containment scope and which systems can be safely isolated without paging additional roles.

Calm Communication: The Status Update Formula

Stakeholder anxiety follows a predictable pattern. Without information, anxiety compounds exponentially. Leaders begin calling individual engineers. Product managers start guessing at customer impact. Each inquiry interrupts troubleshooting and increases coordination burden.

Scheduled status updates solve this problem through predictability. The incident owner commits to a specific cadence—typically every 15 to 30 minutes during active response, with initial updates for high-severity incidents often delivered within 15 minutes—and delivers updates whether new information exists or not. CISA guidance on incident response planning emphasizes that clarity, brevity, and consistency in crisis communications prevent accidental slowdowns and maintain stakeholder confidence.

The update follows a consistent template:

Owner: [Name]

Impact Summary: [Affected systems, user impact, blast radius]

Next Update: [Specific timestamp, typically 15-30 minutes forward]

Current Actions: [What the team is actively doing right now]

This format delivers the information stakeholders need to manage their own responsibilities while protecting the response team from inbound questions. When leaders know the next update arrives in 20 minutes, they stop calling. When product teams understand current impact scope, they can proactively communicate with affected customers rather than waiting for perfect information.

The cadence matters as much as the content. Organizations that commit to scheduled updates—even when those updates report “no new progress, investigation continuing”—consistently receive higher stakeholder satisfaction scores than teams that update only when breakthroughs occur. Research on crisis communication confirms that predictability reduces anxiety more effectively than frequent unscheduled bursts of information.

Status updates should go to a single, designated channel. Email creates version control problems and encourages reply-all noise. A dedicated incident channel with a pinned incident document ensures all stakeholders see identical information simultaneously and provides a single source of truth for the incident timeline.

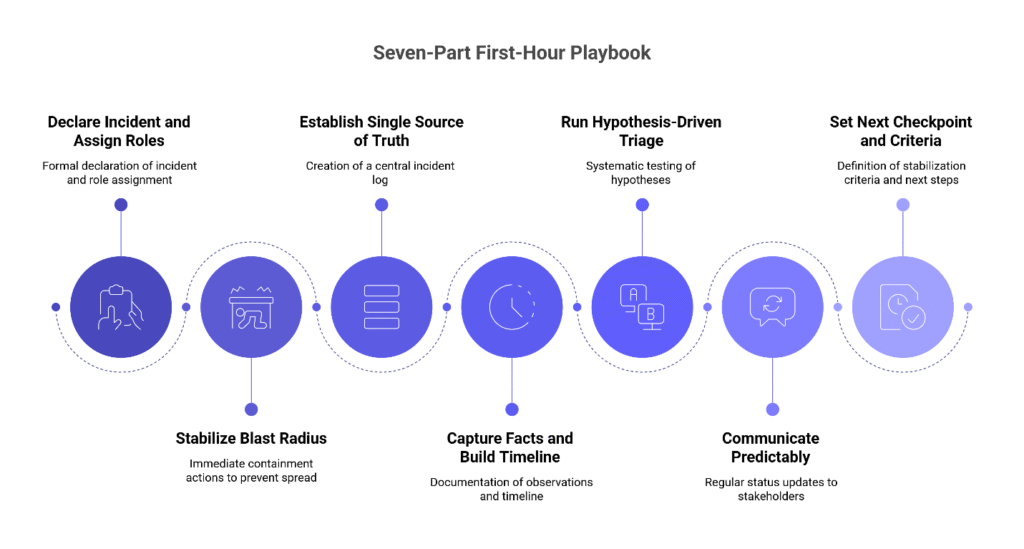

The Seven-Part First-Hour Playbook

Organizations that reduce MTTR without expanding headcount share a common pattern: they execute the same sequence for every incident, eliminating decision latency during the critical opening window. This seven-part playbook provides that structure and aligns with established incident management best practices.

1. Declare the incident and assign roles (Minutes 0-5)

The moment someone identifies a potential incident, they formally declare it with a timestamp and severity level in the designated incident channel. This declaration creates the authority to act and signals to the team that structured response has begun. The on-call engineer immediately designates an Incident Commander, an Operations Lead for technical triage, and a Communications Lead for stakeholder management. If the initial responder is the most appropriate commander, they explicitly claim the role in the channel.

2. Stabilize the blast radius (Minutes 5-15)

Before pursuing root cause, the team determines which systems and users are currently affected and takes immediate containment action. Common moves include rolling back the last risky change, using feature flags to disable problematic functionality, rate-limiting nonessential services, or isolating noisy components. The goal is to arrest harm and prevent further spread, not to achieve elegant solutions. This scoping informs containment decisions and helps stakeholders understand urgency.

3. Establish a single source of truth (Minutes 10-20)

The Incident Commander spins up the war room—whether that’s a dedicated channel, bridge line, or document—and pins the canonical incident log. This log records timestamps, owner changes, hypotheses tested, decisions made, and their outcomes. Maintaining one authoritative record reduces cross-talk and accelerates handoffs, both key contributors to MTTR.

4. Capture facts and build a minimal timeline (Minutes 15-25)

The team documents who is impacted, how they’re affected, since when the problem has existed, and what the current scope looks like. Critically, the log distinguishes observations—actual telemetry, errors, and symptoms—from interpretations and hypotheses. This separation prevents premature anchoring on incorrect theories and drives cleaner decision-making under pressure.

5. Run hypothesis-driven triage (Minutes 20-45)

Rather than investigating all possibilities simultaneously, the team forms two to three likely suspects, tests the cheapest and fastest hypothesis first, and immediately reverts any change that worsens impact. The Operations Lead establishes time-boxed investigation windows and checkpoints every 10 minutes to re-rank hypotheses based on new evidence. Speed comes from disciplined iteration, not guesswork or parallel investigation chaos.

6. Communicate predictably throughout (Minutes 15-60)

The Communications Lead publishes the initial status update quickly—within 15 minutes for high-severity events—and promises the next update time, then meets that commitment. This cadence continues throughout the first hour regardless of progress. The predictable rhythm reduces stakeholder anxiety and protects engineers from context-switching interruptions, improving overall team throughput.

7. Set the next checkpoint and success criteria (Minutes 50-60)

Before the first hour concludes, the Incident Commander defines what “stabilized” means for this specific incident—error rate below a threshold, latency back under SLO, or queue drained, for example. The team assigns owners for the next response phase and documents the plan. They decide whether to continue live triage, implement a workaround, or transition to recovery and root cause analysis.

Following these steps in sequence—every time—transforms the first hour from chaotic firefighting into structured problem-solving. Teams spend less energy on coordination and more on technical resolution. Maintaining accurate configuration standards ensures that runbooks and paging rotas remain aligned with the current system architecture, supporting consistent playbook execution.

Measuring Success Without Adding Headcount

Organizations committed to MTTR reduction need metrics that reveal process effectiveness rather than simply rewarding faster recovery times. Seven measurements matter most for evaluating first-hour discipline.

Time to Mitigation vs. Time to Restoration

Separating these two metrics clarifies which interventions actually reduce customer pain. Mitigation marks when the blast radius stops growing—when containment succeeds and no additional users or systems are affected. Restoration marks full recovery to SLO compliance. The gap between them reveals whether your containment tactics work and which recovery paths consume the most time. Organizations with strong first-hour protocols often achieve mitigation within 20 minutes while restoration may take hours for complex root causes. The NIST Cybersecurity Framework 2.0 distinguishes Respond and Recover functions for precisely this reason.

Time to First Correct Action (TTFCA)

This measures the elapsed time between incident acknowledgment and the first response action that meaningfully contributes to resolution. This might be the right page going out, the correct containment decision, or the identification of the affected system. TTFCA reveals whether the team’s initial response follows productive paths or wastes time on incorrect hypotheses. Organizations with strong first-hour protocols consistently achieve TTFCA under 10 minutes.

First Response Time (FRT)

FRT tracks the minutes from alert trigger to an Incident Commander being on-scene with roles assigned and response initiated. Reducing this interval requires on-call readiness checks, a one-click incident declaration mechanism, and a clearly posted duty roster that eliminates “who’s on call?” delays.

MTTR Trend Analysis

Rather than focusing on individual incident performance, this metric tracks mean time to resolution across similar incident types over quarterly periods. A well-structured first-hour playbook should drive downward MTTR trends even as incident complexity remains constant. If MTTR stays flat despite process investment, the root cause likely involves factors outside the first-hour window.

Handoff Latency

This measures minutes lost when changing owners or transitioning between teams. High handoff latency typically indicates gaps in documentation, unclear role definitions, or poor incident log hygiene. Organizations reduce this metric through a single canonical incident log, explicit “owner now” callouts in the timeline, and ready-to-use handoff checklists.

Update Cadence Adherence

This tracks how consistently incident owners deliver promised status updates. Organizations can measure the percentage of incidents where all scheduled updates occur within two minutes of the committed timestamp. High adherence—above 90 percent—signals that the process has become genuinely internalized rather than remaining aspirational documentation. Poor adherence suggests the protocol itself may be too burdensome or that team training needs reinforcement.

Page Efficiency

This metric examines pages sent per incident and acknowledgment time. Chronic over-paging creates alert fatigue and slow response. Tightening routing rules based on incident type and severity, plus reducing noise from non-actionable alerts, ensures that on-call energy flows to genuine incidents requiring human judgment.

These metrics matter because they connect first-hour behaviors to business outcomes. Leadership cares about MTTR and SLA attainment. Engineers care about reducing chaotic response experiences. Stakeholders care about predictable communication. A strong first-hour playbook serves all three constituencies simultaneously without requiring additional hiring.

Building First-Hour Discipline Through Practice

The first hour resolves the immediate crisis. The days and weeks following should transform that experience into organizational capability. Every incident generates two valuable outputs: a resolution for the current problem and learning material for future prevention.

Post-incident reviews should focus on process adherence before technical root cause. Did the team follow the seven-part playbook? Which steps succeeded? Where did the actual response deviate from the intended protocol? Teams that rigorously examine their own first-hour execution develop progressively tighter MTTR performance over time.

The review should also identify process gaps that the current playbook doesn’t address. Perhaps the incident revealed that a critical system lacks defined ownership in the paging rota. Maybe the team discovered that a specific error pattern requires specialized knowledge that current on-call engineers don’t possess. These observations become backlog items for runbook refinement, not just technical fixes.

Organizations with mature incident response programs maintain a living first-hour playbook that evolves based on real response data. After each incident, the designated owner proposes playbook updates if the current version created friction. These updates go through lightweight review—typically just the infrastructure lead and one other senior engineer—before incorporation. This continuous refinement ensures the playbook remains useful rather than becoming outdated documentation that teams ignore under pressure.

Building this muscle requires practice in low-stakes environments. CISA publishes free tabletop exercise packages that organizations can tailor to their specific environment and run on a regular cadence. These exercises test role clarity, communication protocols, and decision-making under simulated pressure without the cost of real incidents. Teams that commit to structured practice exercises often experience measurable improvements in their incident response effectiveness.

The ISO/IEC 27035 standard for information security incident management emphasizes this learning cycle as essential for organizational resilience. Effective incident response isn’t measured solely by restoration speed but by the rate at which organizations internalize lessons and reduce similar incident recurrence.

Ready to Build First-Hour Excellence?

The first hour determines most of your MTTR. Clear ownership eliminates escalation loops. Paging discipline brings the right expertise online without creating coordination noise. Scheduled status updates protect your team from stakeholder interruptions while building organizational confidence in your response capability.

Organizations that implement structured first-hour protocols often experience notable MTTR improvements as wasted motion gets eliminated and teams shift from working faster under pressure to working more efficiently with clear processes.

Start with a single incident type and build the discipline there before expanding. Choose the most frequent category your team handles—perhaps service degradation or deployment rollbacks—and document the seven-part sequence specifically for that scenario. Run a practice drill where the team executes the playbook against a simulated incident using one of CISA’s free exercise packages. Refine based on what felt awkward or unclear.

After three real incidents using the structured approach, the team will have internalized the pattern. The playbook transforms from external documentation into shared instinct. That’s when you see the MTTR curve shift decisively downward.

Explore the complete first-hour framework in our hub article: “First-Hour Excellence: A Rapid Incident Resolution Framework That Protects SLAs.”

Disclaimer

This guide provides informational frameworks for incident response and does not replace your organization’s specific incident response policy or legal and security requirements.

Our Editorial Process

Content is planned from strategy, double-checked for source alignment, and reviewed for clarity and accuracy. We favor standards-based references to ensure guidance reflects established practice.

By: The Gigabits Cloud Insights Team